Are our favorite movies missing half of the population?

13 Jul 2025I enjoy watching movies to unwind and sometimes dive deeply into recommended films. One movie that had been on my wishlist for a long time was “Oppenheimer (2023)”. When I finally watched it, I was impressed by the direction and performances—my high expectations were mostly met. However, one aspect was deeply off-putting: the overwhelming presence of men talking to other men, making decisions that affect everyone, with women appearing mostly as love interests.

To be fair, “Oppenheimer (2023)” is set in the 1930s and 40s—an era when women were largely excluded from high-level positions. So one could argue that the limited female presence reflects the historical context. Yet this explanation doesn’t fully justify the absence of nuanced female characters or the failure to highlight women’s contributions at that time. This lack of meaningful female representation is not unique to “Oppenheimer (2023)” but is a widespread issue in the film industry. In order to identify and/or acknowledge a systematic issue, we have to come up with a few proxies that are simple, convincing and telling. One such instrument is the Bechdel Test.

The Bechdel Test

The scarcity of depth in female characters led to the creation of a simple but powerful gauge in 1985 through a comic strip, now commonly known as the Bechdel Test. The test originally checks if:

- The movie must have at least two women in it.

- The women must talk to each other.

- Their conversation must be about something other than a man.

There are many variations of the test, but this core idea highlights the minimal criteria for meaningful female representation.

Reflect for a moment on how easy it should be for a film to pass this test. Women make up roughly half the world’s population. Each individual experiences as much drama, conflict, and decision-making as anyone else.

If you identify as a woman, think about the last time you talked to another woman about something other than a man. Hopefully, it’s a common and recent experience. If you don’t identify as a woman, consider the last time you overheard women talking about something other than men. (Yes, discussions about work, hobbies, make-up, or shopping count! And if you want to bring in more stereotypes, be my guest.)

In my opinion, passing this test should be no harder than finding a scene with a tree - women, like trees, are everywhere. Unless the storyline is extremely niche, like a man wrestling a bear in the wild (“The Revenant (2015)”), movies generally have the opportunity to include women in meaningful roles and conversations. Failing the test should rather an exception.

For clarity, passing the Bechdel Test does not mean a movie is inherently feminist or representative of women. It’s merely a starting point to recognize the absence of women figures on screen. And there are quite a few movies which are known for strong female characters, but don’t pass the test, for example, “Gravity (2013)” or “No One Will Save You (2023)”. None of them is not among the top 25 movies though.

IMDb Top 25 movies on Bechdel Test

To explore this further, I examined the IMDb Top 25 movies (as of July 2025) to see if they pass the Bechdel Test. Since I hadn’t memorized every scene, finding the test results lead me to a beautiful corner of the internet - bechdeltest.com. This is where people crowd-vote if and how a movie passes or fails the test. They have a slightly different version of the test in which they expect the two female characters to be named.

The result was worse than expected. The majority of these popular movies fail the test. This implies that around half of the world’s population is either predominantly missing from named roles or lacks authentic, independent interactions among each other on screen. Female characters are often reduced to plot devices rather than complex individuals.

Some movies have dubious passes, which are shown under the category “controvertial”. For example, “It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)” is listed as passing under some interpretations based on brief phone conversations about a child’s cold or money-saving strategies, which skirts the spirit of the test but meets the letter. Here are a few comments verbatim:

Pretty certain Mom and little Suzu’s teacher (mom calls her ‘Mrs [something]’) are on the phone talking about Suzu’s cold and her flower, when dad grabs the phone from mom and mr teacher then grabs the phone from mrs teacher. source

Additionally, in the final scene Mrs Bailey comments the fact that the maid Annie is contributing to the money collection, to which Anne replies that it’s the money she had been saving for the divorce in case she ever got a husband. It’s not talking about a man but about women’s saving strategies! source

Reading these discussions can be both frustrating and entertaining (definitely popcorn-worthy) internet debates - but we shouldn’t lose focus on Alison Bechdel’s original intent: to highlight systematic underrepresentation and not carried away by technicalities.

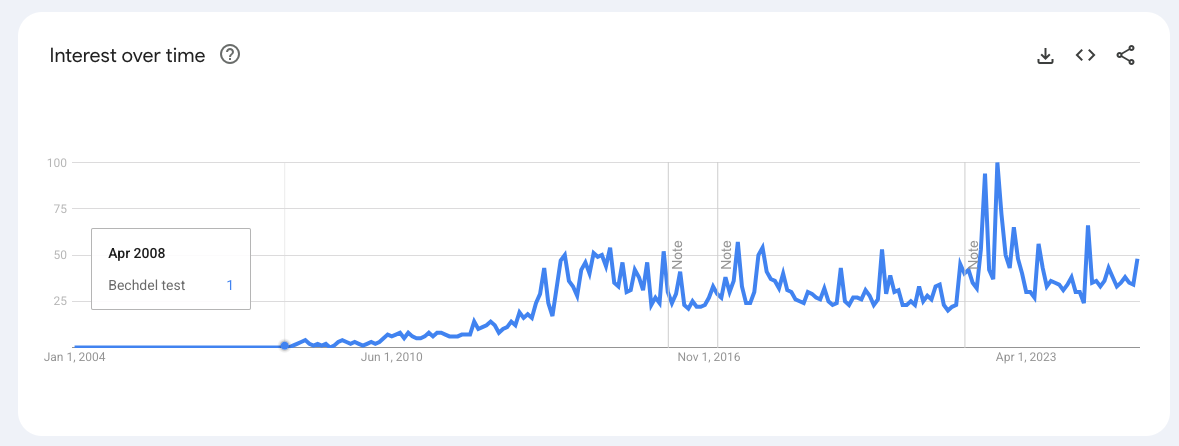

Though the test originated in 1985, it has gained more mainstream recognition only recently, according to Google Trends data, which shows rising interest over the last decade. Still, its insights remain under-appreciated by many.

The distribution of movies passing the Bechdel Test over time captured below by decade shows a steady increase in the number of movies that meet the criteria. Whether it’s due to increased awareness or a genuine effort to improve representation, the trend is encouraging.

Comparison with the “Reverse Bechdel” Test

But wait, let’s not jump the gun here. Unless we look at the number of criteria that are not met, we can’t really conclude that the problem lies in representation of women on screen. A possible explanation could be that perhaps everyone just talks about the opposite sex, i.e., mostly the last criterion is not being met. If that’s our premise, then we should also look at the “Reverse Bechdel” Test (of course, not an official term), which I describe as:

- The movie must have at least two named men in it.

- The men must talk to each other.

- Their conversation must be about something other than a woman.

If a lot of movies don’t pass the “Reverse Bechdel” Test, it might suggest that the issue isn’t just about representation but potentially the obsession of film industry with romantic aspects.

In the same movie set, every film passed this test 100%. Each one of them. Men fight, men drink, men cry, men pray. They discuss emotions, work, money, sports - not just women. In contrast, women mainly appear in relation to men (as wives, daughters, love interests).

I mentioned two movies (“Gravity (2013)” and “No One Will Save You (2023)”) before which have strong female characters but fail the Bechdel Test. Interestingly, they also fail the “reverse Bechdel” Test. While representation has improved in some ways, harmful stereotypes and narrow storytelling persist. The film industry still has a long way to go in embracing diverse, complex female characters and narratives beyond romantic or relational roles.

Final Thoughts

While I think it’s important to acknowledge the progress made in terms of representation, we must also recognize that there is still a long way to go. There are movies which technically pass the test but via a brief two-minute exchange in a two-hour film, pointing to a minimal compliance rather than genuine representation. Focussing on just this test can incentivize movies to simply add such scenes without meaningfully changing the composition of the characters and their stories. For example, Sweden launched a movie certification based on this test in 2013. This simple analysis lead to many meaningful conversations, discussing why are women so poorly represented in the movies? Is it because their stories don’t sell? Is it because the film industry’s story tellers - the directors, producers, script writers, etc. are predominantly men and therefore are completely oblivious to the “other” kind? These are all interesting questions that are too nuanced to be explained easily. But I hope it got you thinking about feminism too. The fact that so many movies fail the “Bechdel Test” does not imply structural bias, but the fact that they only fail the “Bechdel” Test, and barely the “Reverse Bechdel” Test does.

Analyzing this small sample was insightful and sometimes amusing. I hope to extend this analysis to larger, more complicated datasets. What about IMDb Top 250 movies, what about the less popular movies, what about other pseudo-metrics - like % dialogues with female characters and so on to build a 360° view of a movie - these are all ideas I hope to implement and present in the future.

Representation on screen matters - not just for women, but for all underrepresented groups. I would love to watch a superhero movie about an LGBTQ dwarf person - I mean, who doesn’t love a story of someone who rose through all odds to win!